The Doctor Who Wrote the Powerful, Manipulative Playbook for the Anti-Abortion Movement

In DepthIn Depth

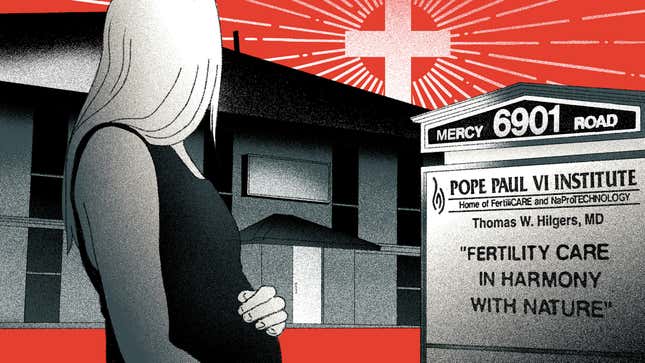

Illustration: Angelica Alzona

The most enduring images of anti-abortion protestors in the ’90s depict murderers and zealots, the thousands of protesters who blockaded clinics in Kansas during Operation Rescue’s “Summer of Mercy” or the 31-year-old man who shot abortion provider Dr. David Gun three times in the back. But another set of activists were creating a more enduring movement in a squat brick office building on the aptly named Mercy Road in Omaha, Nebraska, where research labs shared space with chapels and the chief medical officer, a man named Dr. Thomas Hilgers, kept a wall display he referred to as the “Miracle Baby Bulletin Board.”

Dr. Hilgers, now in his late 70s, has spent his life using his medical expertise to support the anti-abortion movement, publishing books alleging the “faulty science” of Roe v. Wade and training a generation of medical professionals to interpret anti-abortion politics through the language of scientific fact. He was among the first abortion opponents to see that case studies might be better received than pamphlets telling women how they might be judged after an abortion. While state legislators imposed days-long delays on abortion-related procedures, Dr. Hilgers and his staff at the Pope Paul VI Institute for the Study of Human Reproduction built an adjacent form of activism, constructing a medical practice and research facility to offer alternative treatments to what Hilgers refers to as the “highly abortive culture” of mainstream obstetrics and gynecology—a program that could market itself to church leaders as an answer to all their constituents’ tricky questions about how to plan families in accordance with their faith.

Since its founding in the mid-’80s, the Pope Paul VI Institute has grown from a small office into a 14,000-square-foot medical complex garnering nearly $2.5 million in revenue a year. In 2019, the center reported around $1.5 million in tax-deductible donations and is a partner in Amazon’s charity program, Amazon Smile. The institute claims to have trained well over 3,000 medical professionals during the course of its operation and sees up to 900 patients a year. Its influence is global: In 2015, Poland’s health ministry cut funding for in vitro-fertilization in favor of the clinic’s signature—if widely disputed—alternative fertility treatment plan.

The Institute houses a hormone laboratory, an ultrasound center, a clinic, and lecture halls where employees conduct research, treat patients, and train visiting residents, many of whom return to their home states to open affiliated clinics. An affiliated business, FertilityCare Centers of America, oversees 300 clinics in all 50 states. Through its imprint, the non-profit has published hundreds of brochures on “fertility abuse” and how to approach abstinence along with more run-of-the-mill booklets on, for example, breast self-exams.

In its decades of operation, the staff of the Institute has developed alternatives to nearly every aspect of reproductive health

In its decades of operation, the staff of the Institute has developed alternatives to nearly every aspect of reproductive health. The result of Dr. Hilgers’ life’s work has been the creation of a parallel medical system, one formed in opposition to secular reproductive practices that is now, in essence, considered broadly legitimate if not particularly mainstream. It prefigured the modern anti-abortion movement by a generation; few organizations have had such an effect on how anti-abortion activists frame and justify their work. Some of the most high-profile doctors in America pushing pseudoscientific theories about pregnancy and abortion trained there. And the preoccupation with medical science over Biblical mandates typified in an organization like Obria, the network of crisis pregnancy centers that rebranded as an anti-birth-control wellness clinic in 2019 to secure federal funding, was first pioneered at Pope Paul.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-