The Rise and Fall of the Great American Cigarette

In Depth

Cigarettes were widely considered gross and disreputable at the beginning of the 20th century; by the end, they were on their way out of widespread public acceptability once more. In between, they were ubiquitous. The politics of that arc are the subject of a fascinating new work of history.

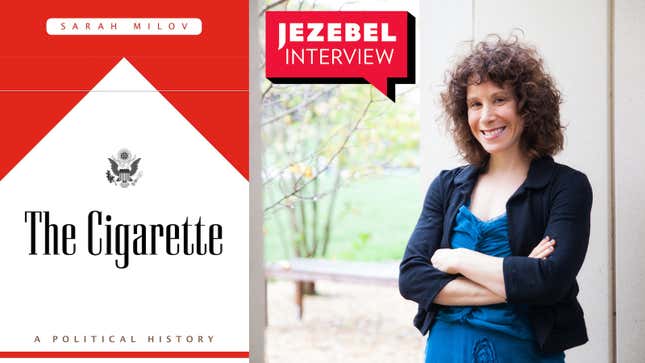

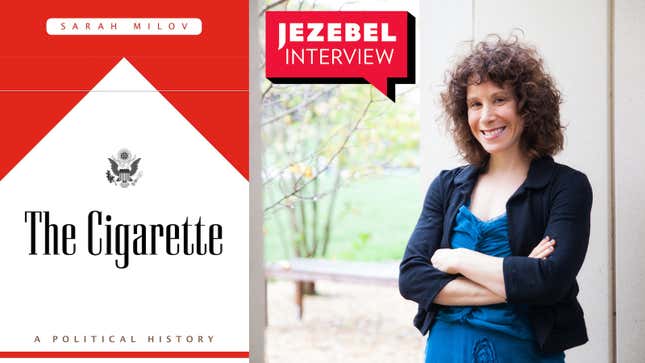

Sarah Milov’s The Cigarette: A Political History refocuses from the much-discussed deceptive actions of the tobacco companies to the politics around their end product. Milov draws out the role of the federal government in essentially fostering the business, for instance through New Deal programs that supported tobacco farmers that lasted long many of the other recovery programs of the time.

She also explores the activist movement—often spearheaded by women—that articulated a concept of nonsmokers entitled to a smoke-free environment and, in so doing, managed to take on a rich and powerful industry that was lying to the country about whether its products were dangerous. But the book also explores some of the tensions in the fight against smoking, and the more uncomfortable reasons why it succeeded, like the fact that part of what it took to drive smoking out of public places was language focused on productivity and efficiency in the workplace, appealing to management’s desire to control its employees. You probably don’t want to be stuck at a desk next to someone chain-smoking Virginia Slims—but I bet we’d all love a few more contractually enshrined and universally observed ten-minute breaks.

I spoke to Milov about her framing of the book and why the political history of cigarettes, as well as the movement that took on the tobacco industry and the unintended consequences for workers.

JEZEBEL: Why a political history? There’s been a lot of writing about the history of the tobacco industry and how completely fucked up it has been, generally. What makes this a political history, and what parts of the story did you choose to illuminate and why?

SARAH MILOV: I think if people hear about the history of tobacco, or the history of the cigarette, they associate that history very strongly and only with the history of corporate deception conducted by the cigarette manufacturers beginning in the 1950s—the half-century-long conspiracy to collude in order to avoid regulation by insisting that the science behind cigarette smoking health was not settled when, in fact, it was. That’s the story. And it’s invoked repeatedly now as the tobacco playbook, doubt-mongering science and the extensive use of scientists for hire as a method of leading an industry that’s now emulated, of course, by big oil, the pharmaceutical industry, etc. The tobacco playbook means a particular kind of history.

I approached this book from a slightly different angle. And in fact, it’s an angle that should make us feel both worse about the history of tobacco, but also maybe more hopeful. Worse in the sense that, if you look over the course of the 20th century, tobacco was not unregulated. It wasn’t that the federal government just couldn’t get its act together to act until the 1990s to try to regulate on behalf of consumers. It’s that beginning in the ’20s, but really getting going in the 1930s, the mechanisms of the government were intended to benefit producers. And in this case, tobacco producers.

The first half of my book tracks the laws and policies that allowed tobacco farmers to achieve a degree of prosperity that they had never achieved before, which later gave rise to the tobacco farmers being an alliance with the cigarette manufacturers, being the more folksy avatar for an industry that had no credibility. But in giving tobacco farmers power—for example, the power to tax themselves in order to fund their own lobbying and promotion organization that went around the world after the Second World War—the federal and tobacco state governments really contributed to the cigarette epidemic outside of the US. After the Second World War, tobacco farmers are organized, and they have money to go to foreign tobacco monopolies and say, we can help you engineer an American style cigarette, buy our tobacco. That’s very much related to government policies, because the whole motive for going abroad is to make sure that the tobacco program that exists in the United States doesn’t have an oversupply.

It wasn’t that the cigarette manufacturers pulled a fast one on America. It’s that the federal government was vitally interested in shoring up the livelihood of a politically privileged constituency, farmers. Honestly, white farmers.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-