These Should Be the Best Days of Your Life

Latest

It would probably make it easier for you if I could pinpoint when this all started. I wish I could show you the date on a calendar, boldly marked with a red X, or find the place on a map.

But I can’t. This howling parasite is tricky like that. All that I can give you are a series of ages and events, and hope that if anything I write here resonates with you, then you might take some comfort from that.

When I was ten I drew a picture of my four best friends. I wrote ANNE IS DEAD across the bottom of the page. My teacher found it and sent me to the principal. She told me that my picture was inappropriate, and I begged her not to call my mother. Nothing else was said.

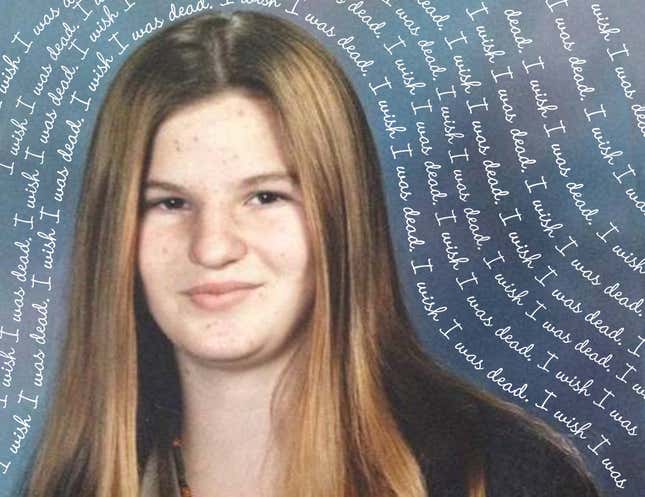

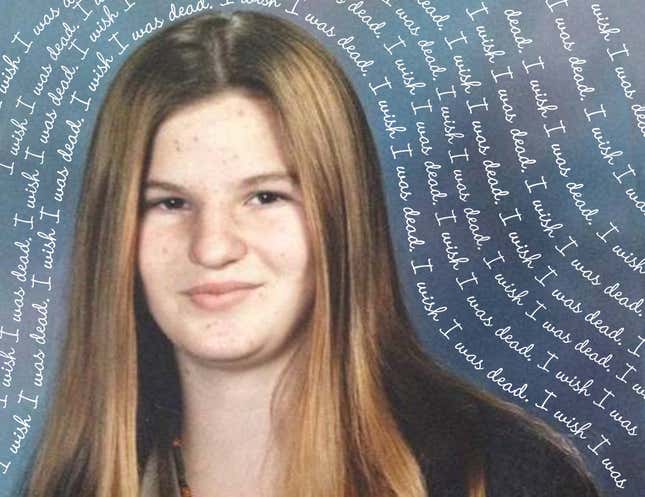

When I was eleven I wrote “I wish I was dead” in my diary. I wrote it over and over, like a spell or a punishment. My diary was an orange Hilroy notebook decorated with a picture of a raccoon that I’d cut out of a nature magazine. I’d thought the raccoon was cute.

When I was twelve my four best friends told me that they’d held a meeting and decided that I was annoying. I was clingy, they said. Needy. The fact was, they didn’t want me around anymore. And just like that, I was cut adrift. For the rest of the year, I spent every recess alone, sitting on a hillside at the edge of the schoolyard with my arms and head pulled into my coat. I didn’t make any new friends.

When I was thirteen I cried all the time. Everyone told me it was hormones.

When I was fourteen I started high school at a place with a prestigious arts program that you had to audition to get into. I thought that it would be a fresh start, that I would be able to shake myself out of this funk and go back to being my real self, whoever that was. Instead, I kept crying. I cried in the bathroom. I cried in the hallways. When I got home I got into bed and cried some more.

I thought that if I could find a boyfriend everything would be better, but somehow he never materialized.

When I was fifteen I told my mother that I thought I should see a doctor. The doctor put me on Paxil and gave me a referral to a therapist. The therapist was an old, bald man with a white beard. He laughed when he read my intake form, where I’d written that I’d been made jaded and cynical by this miserable world. I’d tried to choose grown up words so that he would take me seriously; instead, he asked me if I really knew what jaded meant.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-