Abortion Clinic Escorts Are Putting Their ‘Bodies On the Line’

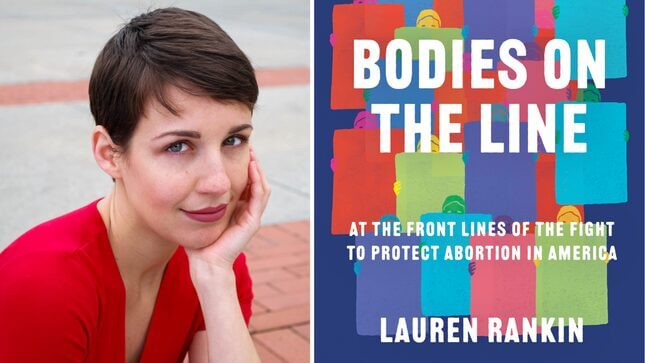

Author, journalist, and clinic escort Lauren Rankin spoke to Jezebel about her new book, and the persistence of anti-abortion violence in America.

AbortionPolitics

Dandy Barrett’s father James had been volunteering as an abortion clinic escort—someone who supports and accompanies patients into clinics, often through throngs of intimidating protesters—for just over a year, in the wake of the 1993 assassination of Florida abortion provider Dr. David Gunn. Then, one summer morning in 1994, Dandy received a call that changed her life: Her father had been shot and killed while entering his clinic’s parking lot.

In the aftermath of one of the worst days of her life, Dandy told journalist Lauren Rankin that she was devastated—but over time, she became more and more motivated to advocate for abortion access and ensure her father would be the last clinic escort to be murdered by so-called “pro-life” protesters.

Rankin’s new book, Bodies On the Line: At the Frontlines of the Fight to Protect Abortion in America, is rife with stories like Dandy Barrett’s, as well as those of abortion providers whose young children have been stalked and threatened by anti-abortion activists, those whose clinics have been burned to the ground and clinic escorts who’ve been kicked, trampled, and nearly run over by anti-abortion zealots.

“Abortion at its core is about people, it’s about people’s dreams, it’s about life—just not in the way that abortion opponents claim.”

Before Rankin became a clinic escort herself in 2015, she told Jezebel she had been reporting on abortion rights for years. But becoming a clinic escort, she says, “showed me this issue in a fundamentally different way.” For the patients who walked by her side into the clinic, only to be screamed at, called slurs, and otherwise harassed or degraded by protesters, abortion wasn’t about politics—it was “about life.” And through all of the harassment and both physical and “psychic violence” that she and other escorts have had to endure, it was this realization that inspired her to continue.

“Abortion at its core is about people, it’s about people’s dreams, it’s about life—just not in the way that abortion opponents claim,” she said. “Everyone knows and loves someone who’s had an abortion, people of all backgrounds. It’s incredibly common. But because we’re told not to talk about it, abortion seems like some deep, dark, dirty secret.” This stigma, Rankin says, has been exploited by anti-abortion activists for years, and it will persist “until we actually start saying the word.”

As Rankin documents in Bodies On the Line, which was released Tuesday, clinics across America experienced a jarring rise of extreme, often physically violent anti-abortion protests in the immediate aftermath of Roe v. Wade, including protesters blockading clinics, chaining themselves to doors, physically assaulting clinic staff, volunteers, and patients, or committing arson and murder. This violence has persisted well beyond the 70s and 80s: Between 1993 and 2016, there were 11 murders and 26 attempted murders of providers by anti-abortion extremists.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-