‘And We Are Free’: The Power of Tarana Burke’s Memoir

With Unbound, the #MeToo founder tells her own story

In DepthIn Depth

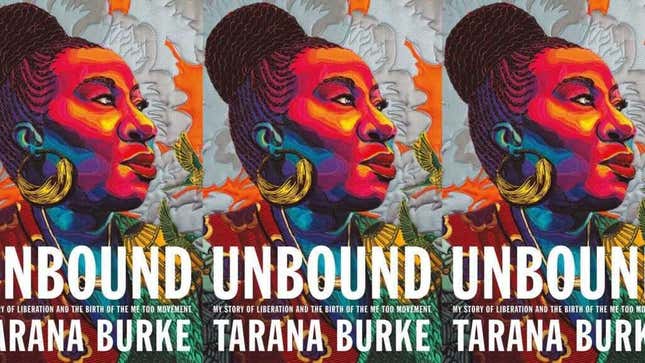

Graphic: Jezebel (Photos: Flatiron Books: An Oprah Book)

Tarana Burke woke up on a Sunday morning in 2017 with a wicked hangover to discover that her life’s work had been turned into a hashtag on Twitter. In a matter of hours, #MeToo had gone from Burke’s personal “work and purpose” to a nationwide phenomenon, without any acknowledgment that Burke had been using the phrase in her organizing work since 2005. The term had been part of Burke’s mission to bring “empathy into the fight against sexual violence” in her own community. But when #MeToo came onto the scene, she wrote, it was “jarring,” adding, “Other than these women [on Twitter] being survivors of sexual violence, none of what was happening in Hollywood felt related to the work I had been entrenched in within my own community for so many years.”

Burke’s memoir, Unbound, is an unwavering, unapologetic claim of ownership of two small yet powerful words that played a crucial role in Burke’s life and, ultimately, in the lives of the women and girls she guided before and after #MeToo became a phrase that bound together thousands of survivors across the internet. In her book, Burke has the first and final say on what it truly means to live and say “me too.” “The story of how empathy works for others—without which the work of ‘me too’ doesn’t exist—starts with empathy for that dark place of shame where we keep our stories and where I kept mine,” she writes.

Burke’s work as an organizer began when she was introduced to a group called 21st Century in high school. “They trained us to strategize and organize, to recognize and fight against injustice and think of ourselves as leaders at any age,” she writes. But the seed of “me too” was planted earlier, when Burke read Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and realized that she was not alone in having been sexually abused as a girl.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-