‘Anna Nicole Smith: You Don’t Know Me’ Takes a Maddening Turn in Its Final Minutes

The new Netflix documentary is shocking and, at times, stomach-curdling, yet only serves as proof we still don't know the pop culture icon at all.

EntertainmentMovies

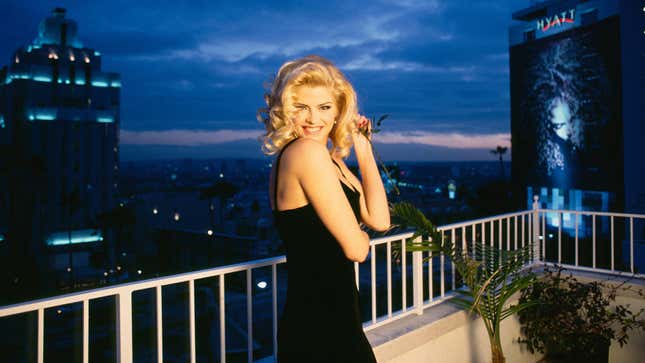

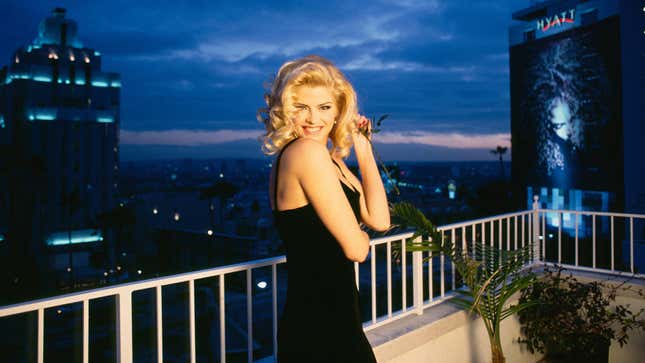

The year is 1993 and Anna Nicole Smith, a small town girl turned sudden superstar thanks to Playboy and Guess co-founder Paul Marciano, is on the phone. Her platinum hair is coiled into neat rows of curlers, lips lined in petal pink, and Texan lilt still unmistakable.

“There’s two major movies that want me at once and they’re both shooting at the same time,” she explains to the person on the other end, lazily doodling hearts and her son’s name on a yellow legal pad. One of the films in question is Chuck Russell’s The Mask. “It’s got Jim Carrey in it…that funny guy,” she says. “I love the script, but the thing is, they offered me…I have a lead role, the lead girl role…this is embarrassing,” she continues. “They offered me $50,000.”

“Business,” Smith sighs, placing the phone back in its cradle. She’s dismayed but resigned. The role will go to Cameron Diaz and land her on the A-list as one of Hollywood’s go-to leading ladies. Smith, however, will book only bit parts as “blonde woman in club,” or, worse yet, crude caricatures of herself. As it’s been revealed time and again, she was quite adept at embodying the latter.

Anna Nicole Smith: You Don’t Know Me, premiering May 16 on Netflix, attempts to discern where Anna Nicole Smith ends and Vickie Lynn Hogan (her birth name) begins. However, if one was hoping for a definitive answer, they won’t get it. The two-hour documentary, directed by Ursula Macfarlane (Untouchable, The Lost Sons), traces the tragic trajectory of the model, actress, and, for better or worse, tabloid magnet with the aid of archival footage, private photographs, and the sometimes quite stunning candor of family and friends. Smith’s story is told with empathy—that is, until its final moments, when the documentary abruptly introduces contradictions about the woman whose likeness was once on the cover of every gossip rag in the grocery store checkout line. Frustrating as that is, I get it. There’s a certain allure to not knowing Anna Nicole Smith.

As her family testifies throughout the documentary, Smith was a person motivated by attention right from the start as she came of age in the Bible Belt. Though it didn’t take much for her to get it, Smith’s native Mexia, population 6,876, was never going to satiate her. According to her uncle, Smith held ambitions far beyond the “life of deprivation” he describes as being part and parcel for the rural town. By her family’s account, in addition to being adored, Smith desired the kind of independence that often accompanies immense wealth. Getting the hell out of Mexia, where she was the object of the affection of dozens of men, was the first step in manifesting that destiny.“We would go to the mall, and I swear to you, there would be 50 men and boys walking behind us,” her now-deceased mother, Virgie Arthur, recalls via voice recording. “Vickie was always beautiful. She was just born beautiful.”

Though, as most things in Smith’s life, her beauty had a way of complicating things—for starters, her relationships, as the documentary outlines. When she was a teenager, Arthur and Smith’s relationship began to chafe, so much so that Smith moved in with her aunt and uncle, who were forced to nail her windows shut to prevent her from sneaking out to be with a 29-year-old man who was infatuated with her. By 17, Smith had dropped out of high school, married a co-worker at Jim’s Krispy Fried Chicken, and given birth to her son, Daniel. The marriage didn’t last—due mostly to her husband’s jealousy. So, with sights set on Houston, she packed up her son and her dreams and finally left without looking back in 1986.

“I want to buy me a whole bunch of land,” Smith said in an early interview. “And I want to create my own house and build it…and build a nursery because I want to have another child. I want to have a little girl.”

All of this, of course, sounds like the same origin story we’ve heard of Smith before. Enter Melissa “Missy” Byrum, Smith’s former friend, personal assistant, and apparently, lover. By Byrum’s account, the buxom blonde was not just a heteronormative hottie hanging on the arms of older men. That Smith was privately bisexual is only the first of seemingly ceaseless bombshells from Byrum, who’s also written a book recounting their time together. In fact, of everyone in the documentary, she provides the lion’s share of enthralling anecdotes about Smith. Byrum speaks plainly about their introduction as co-workers at the Executive Suite, a strip club in Houston (“She couldn’t dance. She looked like an emu trying to fly.”); their friendship (“When we got together, it was combustible. Shit happened.”); and their romantic relationship (“I was her first female lover, I guess. I was definitely in love with her.”).

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-