CHARMED LIFE, TRAGIC DEATH: JFK Jr. and the Last of the Great Magazine-Made Men

In Depth

Illustration: Elena Scotti

John F. Kennedy Jr. died young; whatever his promise, he never achieved it. He wasn’t a popular politician, or a successful actor, or a musician with a closet full of Grammys. And yet, his death two decades ago prompted wall-to-wall media coverage, absolutely dominating the news cycle for days upon days.

Kennedy died 20 years ago this week, in a plane crash off Martha’s Vineyard with his wife Carolyn Bessette Kennedy and her sister Lauren. It was a perfect media story, an instant narrative arc. After decades cast as a hunky heir to a great dynastic legacy, Kennedy died young, headed to a WASPy summer destination. There was even an element of classic Aristotelean tragedy, since the accident was likely due to the fact that Kennedy chose to fly without an instructor, despite being inexperienced flying on instruments, meaning when the weather quickly deteriorated he didn’t have the skills to get safely to the ground.

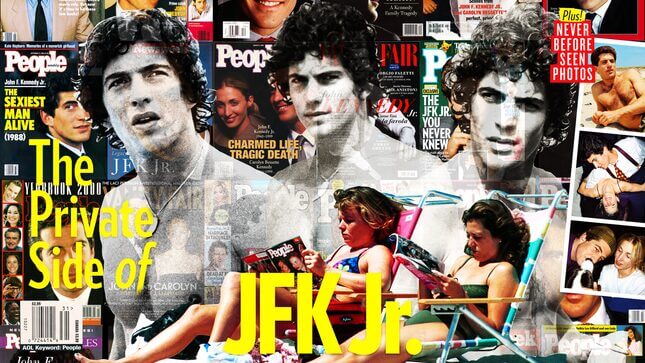

Kennedy’s death was perhaps the last great celebrity story of its era, triggering a flood of covers on magazines from Newsweek to Time to People, as well as a slew of commemorative magazines, full of tributes to a man positioned as an American prince. The August 2, 1999 cover of People said it all: “CHARMED LIFE, TRAGIC DEATH.” It was the end of an era, but not in the way that the money-minting, blockbuster popular People realized. It was a high water mark for celebrity magazines’ place in the world, and for an entire model of celebrity.

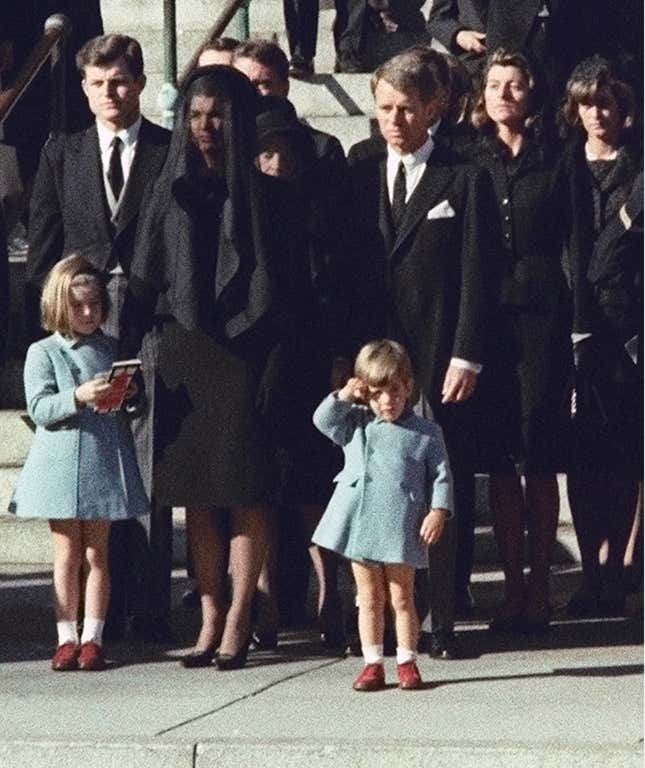

A highly specific set of circumstances, both cultural and chronological, combined to make JFK Jr as famous as he was, but it’s impossible to separate his anointed place in American culture from the media that so loved him, especially magazines. The internet has completely transformed the way we consume information, so it’s easy to forget the power of general-interest magazines, like Time and Life, during the midcentury—and the Kennedy family looked very, very good in those pages. First, there was his childhood as “John John,” the adorable toddler of a young, photogenic president; his place in the national consciousness was cemented by the famous shot of Kennedy saluting his father’s casket. The image would follow him for the rest of his life, even as he repeatedly reminded everyone who asked him that he had no memory of the moment, because he was three years old.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-