Hello From the Royal Wedding, Where I'm Chasing the Rom-Com American-Princess Dream

Latest

London—As somebody whose long-running fascinations include fairy tales, romance novels, and the stubborn persistence of monarchy, how could I possibly miss the opportunity to get as close as possible to that rarest of birds: a real, live American princess?

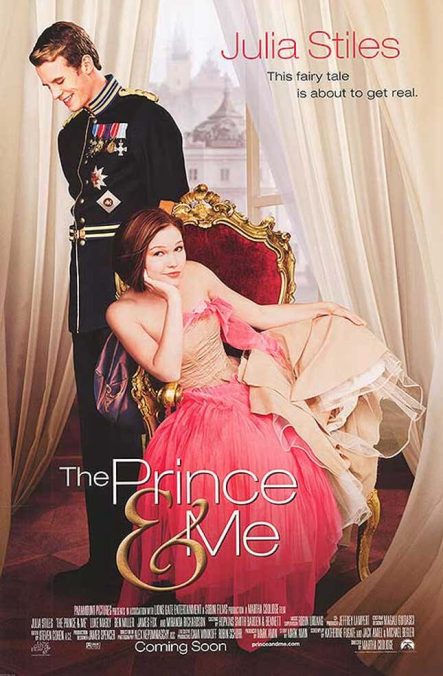

Media from the United States will be a particularly large presence in Windsor for the royal wedding on May 19. No surprise there: Many Americans, myself included, have an odd fascination with the contradictory notion of an American princess. The most famous example is probably Grace Kelly, whose wedding was an utter media circus. Nothing fit the prevailing mood of the 1950s quite like the image of the Academy Award winner looking demure and regal in her wedding ensemble, turning her back on Hollywood for Prince Rainier of Monaco. Decades later, Harry and Meghan’s story has its own messages about our current cultural moment. It’s almost uncanny how much their romance fits with a modernized version of the trope, revamped for a generation that grew up alongside the groom and his brother.

I’ve come to England partly for the priceless souvenirs, the bragging rights, and the opportunity to live on warm scones for a week straight. But I’m also looking for deeper insight into the creation and embrace of a very modern fairy tale.

Admittedly, so far, I am mostly just jet-lagged into oblivion, having slept perhaps three out of the last 36 hours and careening from experience to experience: loading up on Markle-obsessed tabloids at a W.H. Smith; popping over to the publicly accessible parts of Kensington Palace for a selfie at the Sunken Garden, where Harry and Meghan did their first photo call as a publicly engaged couple, tasting a version of Harry and Meghan’s wedding cake at the attached cafe (delicious); and finally, walking into Harrod’s, getting overwhelmed, and walking right back out.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-