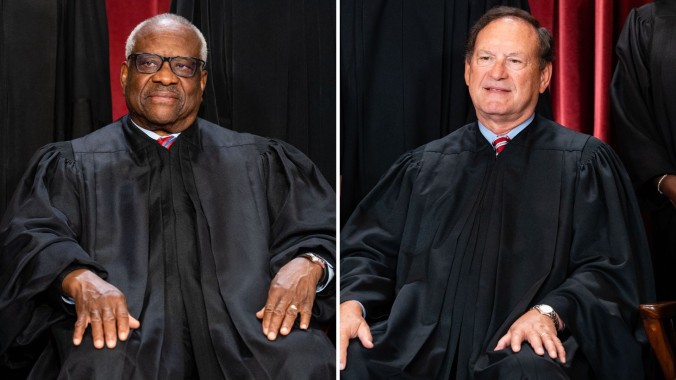

Justices Alito and Thomas Were on Suspiciously Good Behavior Today

The Supreme Court sounded like it might actually rule in favor of a South Carolina Planned Parenthood affiliate in a fairly wonky case, but that wouldn't mean they're suddenly in favor of abortion access.

Photos: Getty Images AbortionIn DepthPolitics

On Wednesday morning, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case about whether people with Medicaid can sue a state for blocking them from getting care at a qualified provider who accepts the insurance. The provider in this instance is Planned Parenthood, which South Carolina tried to kick out of the program in 2018 because it also provides abortions, thus the lawsuit has national significance. A ruling for South Carolina could lead other states to kick abortion providers out of Medicaid, where they provide birth control, cancer screenings, and more.

After more than 90 minutes of arguments, it sounded like Justices Amy Coney Barrett, John Roberts, and maybe Brett Kavanaugh could side with the three liberal appointees in favor of Planned Parenthood South Atlantic on this very technical issue of whether Medicaid patients can sue states. If they do rule that way, it does not mean they’re protecting abortion or birth control—but those three justices would probably love such headlines. (A ruling isn’t expected until late June.)

The possibility of this court siding against an anti-abortion plaintiff may sound surprising, but it would be consistent with a 2023 decision called Health and Hospital Corporation v. Talevski that said Medicaid patients can file lawsuits to enforce their rights. What was even more strange was the fact that Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, the court’s two biggest abortion haters, were mighty quiet today, and we have some theories about why.

But first, the arguments. John Bursch of the far-right Alliance Defending Freedom argued on behalf of South Carolina that Medicaid patients can’t sue the state because they don’t have a right to choose any qualified provider. He claims this is because the specific word “right” doesn’t appear in that portion of the Medicaid Act. In South Carolina’s opinion, the state chooses providers who are qualified, patients pick from that list, and they can’t sue over someone being taken off that list.

Bursch also argued that Medicaid patients could sue if a qualified provider denied them services. Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that if a provider can’t offer the desired services to begin with, there is no denial, and the patient can’t sue. It’s a legal catch-22.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-