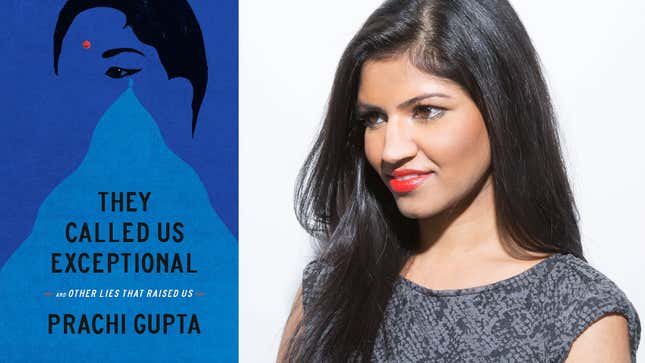

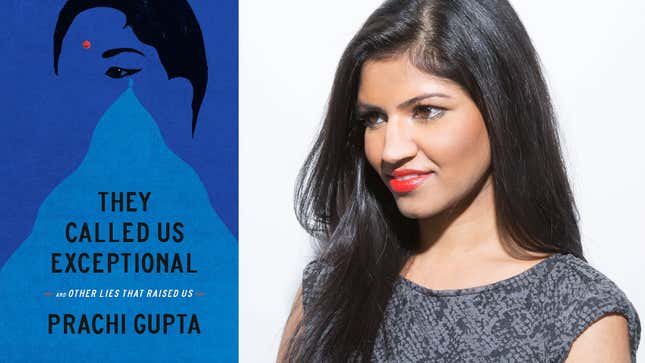

Prachi Gupta Smashes the Model Minority Myth in Her Devastating Memoir ‘They Called Us Exceptional’

With Jezebel, Gupta discusses her "dysfunctional" family and living a double life: "I questioned my sanity almost daily."

BooksEntertainment

Prachi Gupta never planned to write a memoir. “I’m a reporter and I prefer writing about other people,” she explained to Jezebel in a recent Zoom. But the death of her younger brother Yush in 2017, and her subsequent discovery of his men’s rights activism and the cause of his death (a blood clot after limb-lengthening surgery) led to her award-winning investigative essay “Stories About My Brother,” published on Jezebel in 2019. “I had to turn that into something that I felt like could heal myself and help heal other people,” she recalled. “And it was the response from Jezebel commenters, readers, people who found the essay and reached out to me, that made me realize that I need to tell my full story, because I think there’s a lot here that could help other people feel less alone, too.”

The full story from the Jezebel alum arrives in stores Tuesday. They Called Us Exceptional is a prequel of sorts to “Stories About My Brother” insofar as it contextualizes Yush’s politics and attitudes with an in-depth description of his and his sister’s upbringing. Patriarchy begins to look like a chronic condition in light of her father’s behavior. Her father, she writes, was strict, intimidating, and humiliating. His temper sometimes manifested in physical or emotionally manipulative ways (Gupta uses the word “abuse” sparingly). Her mother mostly backed her father up, though she bore the brunt of his rage as well. Gupta kept this mostly hidden, putting up a front for the various racial groups she navigated in her life as an Indian-American girl then woman. “Everything in our lives had fallen into place the way that we’d always dreamed. We had perfected the delicate alchemy of culture, family, and work that resulted in happiness and success in America,” she writes of the facade. Achievement provided a way to organize and control life in the face of racism. “When we had nothing to throw back at the slurs thrown at us, when we had to silently swallow the humiliation of knowing that we were inferior in our own country, Yush and I found solace in the idea that success was part of our destiny. The belief that we were exceptional protected us,” Gupta writes on what she deems the model minority myth.

They Called Us Exceptional, written in the second person addressed to Gupta’s estranged mother, is a synthesis of personal storytelling and cultural reporting. It’s the product of diligent journaling and research, as well as interviews with mental health professionals and family members like Gupta’s aunt and uncle. It’s a vivid and precise story of survival. “In many ways I feel lucky and grateful, because I could have gone down a very different path,” Gupta told me. “I’m okay and I feel very grateful for that.” What follows is an edited and condensed transcript of our conversation.

JEZEBEL: Writing in the second person is such a rare, bold choice. Did anyone ever try to dissuade you from it?

PRACHI GUPTA: No, it was the opposite. I mean, it was a risk. To have a book like this published by a commercial publisher, I couldn’t have imagined it five, 10 years ago: A book that’s written in the second person addressed to an immigrant brown woman—an immigrant, Indian woman—that ties in research and history and centers the experiences of an Indian woman and an Indian-American woman. I think it was the strength of the proposal, but also the relationships that I had built with [journalist and Crown Publishing VP and executive editor] Madhulika Sikka and the writing that I had done before. But also the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests and the awareness over racism and lack of diversity in publishing I think that really started a change, at least at that moment.

I really appreciated the cultural reporting, but at the same time, and I don’t want to sound crass when I say this, but there’s a juicy story here. Familial strife is the stuff of Greek drama. I wonder how aware you were that you were not just creating something that was culturally relevant, but that you were crafting a yarn.

As a writer putting out a book, of course I thought about turning my life into a narrative. It’s a weird thing to do. But as writers, that’s part of what our job is. Especially as a memoir. It’s not my journal. It’s not a documentary. There’s a story here with a narrative and dramatic arc. And how do I tell that story? By trying to be as honest as possible. I didn’t want to create trauma porn. I was very sensitive to the fact that some people might read this and just gawk. Some people might be like, “Oh, I want the sensational value.” There’s something that feels very humiliating about that. I don’t want to share my life story just as gossip fodder. I can’t control how people perceive it and read it, and I’m sure some people will read it that way. My way of sort of mitigating that was that every bit, every detail that I put in there, whether it would be seen in a positive light or a negative light, serves a purpose in the story that I want to tell about how we prioritize external validation and outward achievement in this country over our sense of internal peace and what that costs us.

You know, personal stories are the vehicle for change. There’s a reason why these Greek dramas stay with us and get passed down generations. Like sure, there is a sensational aspect to them. But I think stories are how we interpret the world. And stories are what give powerful institutions their power. And when we understand how those systems work and the stories that support those institutions—like the model minority myth, this idea of Orientalism that I talk about in the book, the stories that uphold racism and patriarchy and capitalism—we can undo them and write new stories. And that’s ultimately the reason that I had to share my full story as honestly as possible.

Every single detail serves a purpose in the story that I want to tell about how we prioritize external validation and outward achievement in this country over our sense of internal peace and what that costs us.

When you talk about avoiding trauma porn, I sensed that your writing was extremely careful, down to the syntax. The word “abuse” is not mentioned until 148 pages into the book, and then it’s like 184 pages when it’s used to describe your father’s behavior.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-