The Abortion Stories We Don’t Talk About

A year after Roe was overturned, women who were unable to get abortions are giving birth to babies they weren't prepared to have.

In Depth

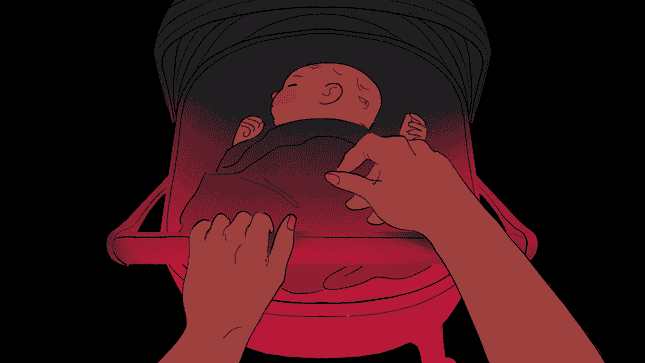

Illustration: Vicky Leta

A few weeks ago, a very busy abortion provider in Washington state had open slots on her schedule, and she wasn’t relieved—she was gutted. The independent clinic where Mollie Nisen works has been “incredibly overwhelmed” with patients since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade one year ago, and the need for abortions hasn’t stopped. She worried these missing patients would be forced to stay pregnant.

“The fact that I’m not seeing them makes me think they’re not getting the care that they need, and that is really scary to me,” Nisen, a family medicine doctor and fellow with Physicians for Reproductive Health, told Jezebel.

She’s thinking about these people all the time—even on the days she’s slammed. On a single day this spring, Nisen did procedures for patients who traveled from seven different states. She’s seen people from Idaho and Alaska and as far away as Texas and Alabama. “Every time I have someone who is able to fly across the country to come see me, I think about all the people who are stuck at home and unable to access those resources.”

But this isn’t even the worst feeling Nisen experiences. No, that’s having to tell some patients who do make it to the exam room that they’re too far along for her to perform an abortion in the state—something that is happening more often post-Dobbs, the case decided last June. “There’s nothing more devastating to me as a provider that is so focused on having people do what is best for them and their families,” she said. “I see the amount of distress this causes. … Continuing with a pregnancy that they’re not connected to is really painful for people.” Nisen can refer them to the few all-trimester abortion clinics in the country, but she never knows if they actually make it. Abortion procedures not only get more expensive later in pregnancy, but people would also need to pay for yet another trip, and take more time off work. You may as well be telling them to fly to the moon.

Women unable to get abortions after Dobbs are giving birth to babies they didn’t want to have, and we’re barely talking about them. I read almost everything about abortion and I can only recall two such stories: That of a 26-year-old Black mother in Jackson, Mississippi, who wasn’t ready to have another child, and a white teen who had twins after Texas’ pre-Dobbs ban halted most abortions in 2021.

What we are hearing are the horror stories trickling out weekly, if not daily, of women across the country who wanted to have children but suffered terrible fetal anomalies or miscarriages, and almost died when hospitals initially denied them the abortions they needed to survive. Media outlets—including Jezebel—cover these cases because they represent the visceral, high-stakes consequences of abortion bans: Pregnancy, whether it’s intentional or not, can be life-threatening and abortion is life-saving healthcare. You know what else is visceral? Not being able to pay your rent because you have a newborn the Supreme Court coerced you into carrying. Stitches on third- and fourth-degree vaginal tears from a baby you didn’t intend to have. And though circumstances like a woman who has three kids and can’t afford more, or simply doesn’t want to be a parent, seem like more “mundane” reasons to seek an abortion, as Nisen called them, any forced pregnancy is a horror story of its own.

The people who are forced to stay pregnant

In just the first nine months after Dobbs, more than 25,000 people were unable to get an abortion from a provider, per reporting from the Society of Family Planning. It’s unclear how many of them remained pregnant against their will or self-managed an abortion. But even if, for argument’s sake, you assumed that half of those people took abortion pills and half gave birth, that’s more than 12,000 Dobbs babies—and counting.

Nisha Verma, an OB/GYN and abortion provider in Georgia, said that, pre-Dobbs, her state used to see a lot of patients traveling from other areas of the South, but now that there’s a six-week ban in effect, she has to turn away even in-state patients every week, often multiple times a week. She can tell patients who are too far along if self-managed abortion is an option and let them know about abortion funds, but it was already so hard for them to get to her clinic in the first place. She recalls a patient from rural Georgia in her early 20s who already had children. Her grandmother came with her to the appointment, but she was beyond six weeks, and Verma had to turn them away. “When they were leaving the clinic, her grandma asked me if I could help them with parking, because they didn’t have money for parking and gas to get home,” she told Jezebel. “Getting out of state can feel just completely overwhelming for people.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-