The Future of Sex Work Starts Now

Politics

Kate Zen, 32, was a student at Columbia University when she began to do sex work to meet her economic needs. “Even though I was a scholarship student, I struggled to cover all of the costs,” she told a scrum of reporters near City Hall in Lower Manhattan Monday morning.

But in one terrifying instance, Zen says she was assaulted after responding to an online advertisement. “I was beat up, had all of my wages and personal property stolen by this person, and was forced to do sex work without a condom,” she recounted. “Afterwards, when I reported the incident to a police officer, he told me that since I was engaging in illegal activity I may not look sympathetic as a victim.”

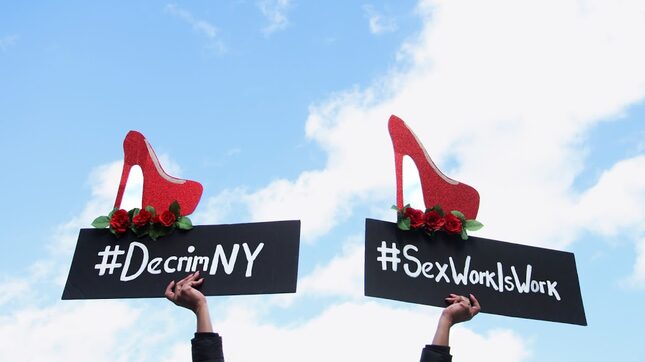

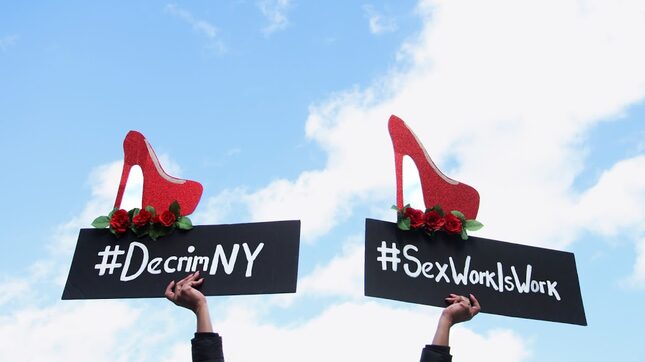

Zen is now an organizer with the sex worker-led coalition Decrim NY, and wants her personal experience to illustrate the danger of working in a criminalized industry where the role of law enforcement has historically been to arrest—not protect. This could change, she says, with Monday’s introduction of the Stop Violence in the Sex Trades Act, first-of-its kind state legislation that would decriminalize the consensual adult sex trade in New York.

The 27-page act—co-sponsored by Manhattan Assemblyman Dick Gottfried and Brooklyn Senator Julia Salazar and drafted in collaboration with Decrim NY—would repeal and amend a slew of penal code sections to decriminalize sex work, while also preserving all mechanisms for prosecuting the trafficking of adults or minors (which by definition must include elements of force, fraud or coercion). It also aims to address other consequences of criminalization, from eviction to burdensome criminal records.

It is a vision without precedent. (The proposal’s closest cousin is a far-reaching decriminalization bill recently re-introduced in Washington, D.C.) The term “decriminalization” has been invoked frequently this year, but imprecisely. California Sen. Kamala Harris made headlines as the first 2020 candidate to call for it, but the platform she detailed isn’t actually decriminalization at all. The sex trades as a whole would continue to be policed, even if certain charges around the sale of sex were eliminated.

“The discussion we are having now is not about morality. It is about economic justice.”

Audacia Ray, a member of Decrim NY’s steering committee and longtime advocate for sex worker rights, pored over state law to help draft the act. Some of these laws “were written in the Victorian Era,” she says, pointing to terms like “bawdy house,” and “lewd persons.”

“They were created to police morality,” she says. “And the discussion we are having now is not about morality. It is about economic justice.”

Though they expect a long fight, advocates and legislators hope the Stop Violence in the Sex Trades Act will serve as a model for other states. Crucially, the bill takes direction from those who have experienced the harms decriminalization would correct—sex workers themselves.

Senator Salazar acknowledged this Monday. “It’s always important to remember that it took years of sex workers fighting… for us to get to this moment,” she said.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-