These Musicians Were ‘Canceled,’ But People Kept Listening

Nielsen Music provided U.S. streaming data to Jezebel for Jackson and a host of artists mentioned in this piece.

Entertainment

Illustration: Jim Cooke, Photo: Shutterstock

Here are some places I heard Michael Jackson’s music this year, after the two-night run of Leaving Neverland in early March: At a Chili’s in Las Vegas’s McCarran International Airport (“Rock With You”), at a “haunted” indoor mini-golf course in Colorado (“Thriller”), at a friend’s 40th birthday party in a South Jersey bar/restaurant (“Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough”), at the Starbucks across from the G/O Media office (“The Way You Make Me Feel”), in a bathroom at work (“Billie Jean”), in a cab in Barcelona (“Shake Your Body”), during a Barry’s Bootcamp class (a dubstep remix of “Beat It”), in an Uber in Brooklyn (“Bad”), in the Todd Snyder store on Madison Park in Manhattan (“Say Say Say”), before Mariah Carey’s recent Christmas show in Atlantic City (“Give Love on Christmas Day”). Had I heard him at Disneyland when I visited in June (and for all I know, I could have and simply not parsed him out of the Disney sensory overload), you’d have essentially a map of my travels in 2019.

At the beginning of this year, Jackson’s cancellation seemed inevitable. When news broke about Leaving Neverland’s marathon of horrors, in which pedophilic grooming and sexual abuse were alleged by two men who were close to Jackson as boys, I felt put out. I was annoyed I’d have to revise my listening habits as a result of a cultural reassessment of Jackson, a mainstay of my musical rotation for decades no matter where my general taste had otherwise shifted. But all of this hand-wringing was for nothing. Deleting Jackson turned out to be easy; after watching the doc, I lost my appetite for his music completely. There was no struggle, no self-centered agonizing, no sneaking in “Remember the Time” when I didn’t think anyone was paying attention. It felt like a clean break. One day I was a person who listened to Michael Jackson. One day I was not.

But virtually everywhere I went, there he was. According to data, my anecdotal experience was not aberrant. In October, Billboard reported that Jackson’s airplay had indeed dropped this year, though the superstar was hardly persona non grata on the airwaves: In the four weeks leading up to the broadcast of Leaving Neverland on HBO, Jackson averaged 14,000 spins per week at radio, but in the 31 weeks after the airing of the two-part doc (through the week of October 3), he was down to an average of around 11,000 spins. His presence has been reduced, not outright banished. (Keep in mind that because of “Thriller,” Halloween is MJ season, and these numbers don’t reflect the possible holiday uptick in airplay.)

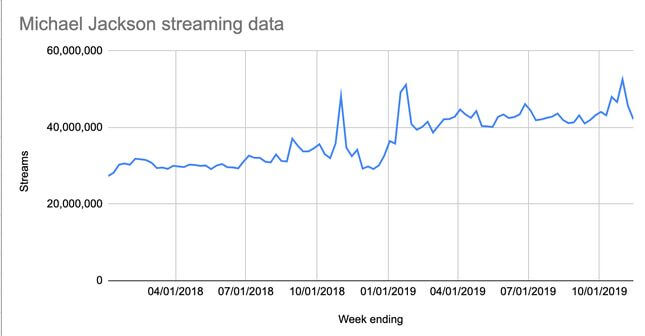

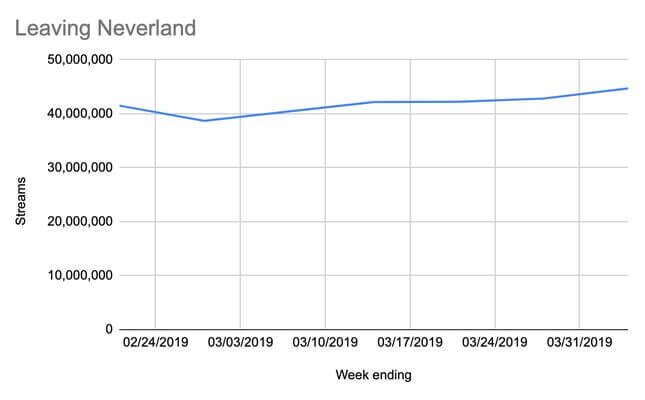

More importantly, though, Jackson’s streams rose this year. If the radio is a democracy-dictatorship wherein the audience (through requests and listener feedback) has nominal say in what the powers that be allow on-air, streaming is the purer democratic metric, a direct indication of demand from listeners. And what they demanded this year was Jackson, whose streams rose 22.1 percent in the 31 weeks after Leaving Neverland aired. (Billboard also pointed out that this figure outpaced the streaming industry’s 21.8 percent growth. By virtue of the fact that more people are streaming, more streams wouldn’t necessarily signify a growing demand for an artist. Jackson’s gains are high enough, however, to suggest a growing demand.)

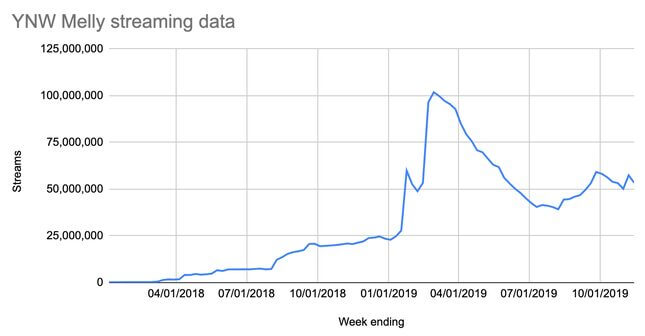

Nielsen Music provided U.S. streaming data to Jezebel for Jackson and a host of artists mentioned in this piece. Here’s a visual of Jackson’s streams spanning all of 2018 through the week ending November 14, 2019:

In fact, the documentary had little, if any, impact on Jackson’s streams at all. It aired March 3 and 4 on HBO in the U.S., and later that week in the U.K.

Looking at the raw data of streaming music is enough to expose the conceptual fallacy of ‘cancel culture.’

This effect isn’t an aberration either. This year, and during the ones that immediately preceded it, recording artists accused of sex crimes and other destructive, antisocial behaviors were able to sustain and in some cases launch careers in the wake of the media coverage of the allegations and ensuing scandals. Looking at the raw data of streaming music is enough to expose the conceptual fallacy of “cancel culture.” To subscribe to the notion that the public readily exerts its power to defrock a celebrity is to believe in a black-and-white binary, the absolute polarity of good and bad, the neat societal organization of punished and free. The truth is messier. Those who believe in and decry cancel culture also miss a crucial point: In order to enact its power, the public must have the will to do so.

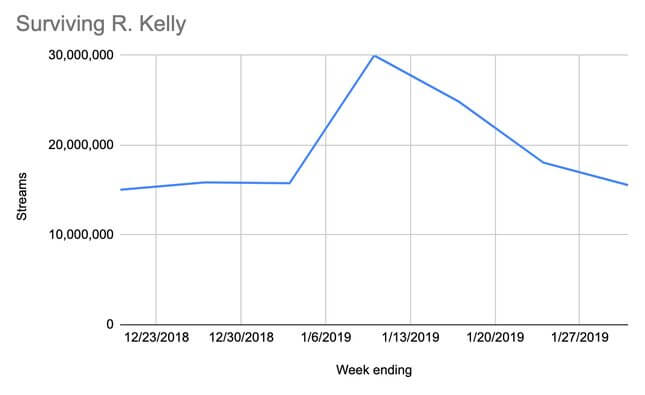

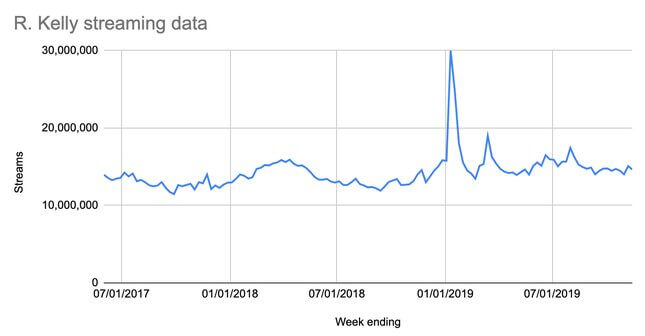

In fact, there are numerous examples of alleged transgressions seeming to attract audiences, not repel them. Take R. Kelly. His ability to sustain an active career in music despite allegations of sexual abuse of underage girls that go back decades is one thing; that his streams jumped 116 percent the day of the final airing of Lifetime’s Surviving R. Kelly docuseries is quite another. Billboard reported that Kelly’s streams sat at 1.9 million on January 2, the day before the three-day broadcast event that detailed allegations of Kelly grooming and raping underage girls and running a sex cult, among other things. By January 5, Kelly’s streams were up to 4.3 million. In terms of weekly figures, he nearly doubled his streams from about 15.8 million the week ending January 3 to about 30 million the week ending January 10.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-