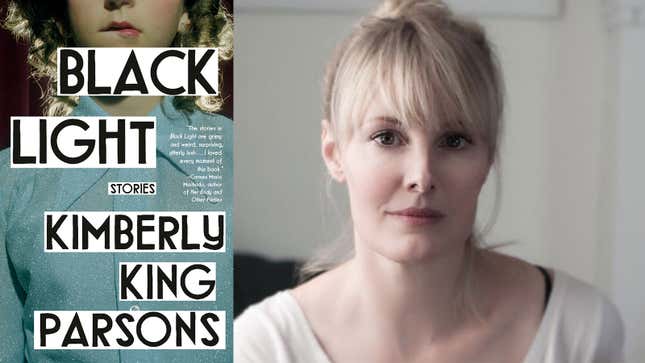

Writer Kimberly King Parsons on Bodies, Blood Banks, and Her New Book of Uncanny Short Stories

In Depth

“Dark” is a word Kimberly King Parsons often uses to describe the short stories collected in her first book, Black Light. But make no mistake: These are not horror stories. They don’t follow any particular gothic tradition, they frequently take place underneath the blazing Texas sunshine, and if they suggest a threat of death it’s only of the ambient variety that is implicit in any excavation of human condition. Parsons likes the word because, as she told Jezebel, her stories deal with “edgier themes or maybe things people don’t typically like to investigate, parts that people like to keep hidden.” The darkness, then, is straightforward: These are themes, characters, and observations rarely discussed in the light of day.

In her dozen Black Light stories, Parsons beams us into scenes of class struggle in private school for girls, through an outdoor fantasia of neighbors’ lawns that provide a refuge to a pair of young siblings from the instability of domestic life with their mentally ill mother, into the minds of two office co-workers with eating disorders and generalized misanthropy, into the gruesome storytelling of a young child who’s coping with the estrangement of her parents. Parson’s prose is spry in its curdled wisdom (“I’ve had almost no loss in my life, but I still believe we’re always in between tragedies, that anything good is a lull before the next devastation”) frequently hilarious (“If it weren’t for the woman’s head, she could be a model”), and generous in its poetry (“When she lets it, Trish’s voice puts a fullness in you that is beautiful and awful, makes you feel like a glass of something waiting to be spilled”). So honed is Parsons’s craft that she can do vagueness specifically: The connection between two teenage girls that’s somewhere between obsessive companionship and all-out romance in “Glow Hunter” she describes as “this electric something.”

I felt a strange simultaneity when reading most of Black Light’s stories: I didn’t want them to end but couldn’t wait for the next one. Rarely is it such a joy to spend time with people who are so fucked up. Parsons, who was born in Lubbock, Texas, and now lives in Portland, worked on these stories from 2005 to 2018. Many of them came as the result of her “cheating on the novel” she was writing that her heart wasn’t in. The resulting stories are frequently linked in their themes and subject matter, the primary being “the idea of everything changing before your eyes but it was there all along,” according to Parsons.

“Getting to the true, un-self-conscious version of yourself I think is the goal for all of them,” Parsons told Jezebel regarding her characters. Our interview has edited and condensed for clarity.

JEZEBEL: Many of your stories share common themes and concepts—storytelling is one. Do you have this sense of your own consistency as you’re writing, that you’re creating multiple pieces of a unified body of work, or is each story its own universe and such commonalties are inevitable as they’re all coming from a single person (you)?

KIMBERLY KING PARSONS: I think I return to the same obsessions and preoccupations over and over again and writing about them doesn’t seem to relieve the infatuation. I write them as standalone. I wasn’t putting them together as a collection initially, but I come back to those same things over and over again that seem to fascinate me. Storytelling is one of them. Hotel rooms come up quite a bit. Or secrets and game-playing.

The primary failing of the human body is that it only allows its inhabitants one perspective. In this book, you jump into the minds of over a dozen characters. That’s a primary function of a short story collection, even more so than in novels. The ability to have multiple points of view strikes me as something like godliness. Does writing these stories make you feel powerful?

I feel kind. I feel like I’m open-minded and I’m open to experiences and I’m open to these characters that are maybe people who haven’t had voices. It makes me feel like a better person to try to inhabit those heads, those thoughts. If there’s godliness, it’s in the idea of loving every person or wanting to enter every person’s headspace, however fucked-up it is. Every single person is living a life as rich and vivid as your life, and we can plunge into these different heads and experience the way they experience the world.

Every single person is living a life as rich and vivid as your life

Does that always feel good? Is it ever emotionally challenging?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-