Britney Spears’ Memoir Is a Riveting, No-Bullshit Call for Compassion

The Woman In Me is required reading for anyone who has ever cared about Spears or the condition of fame.

BooksEntertainment

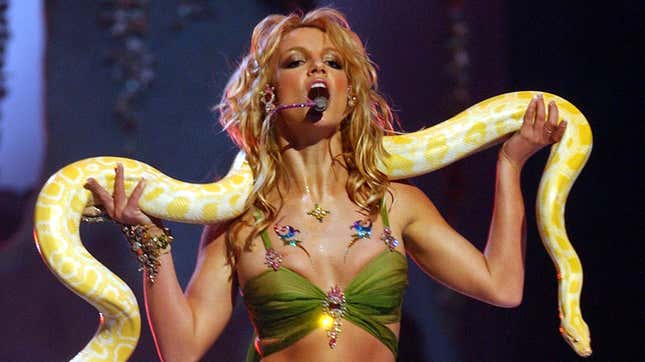

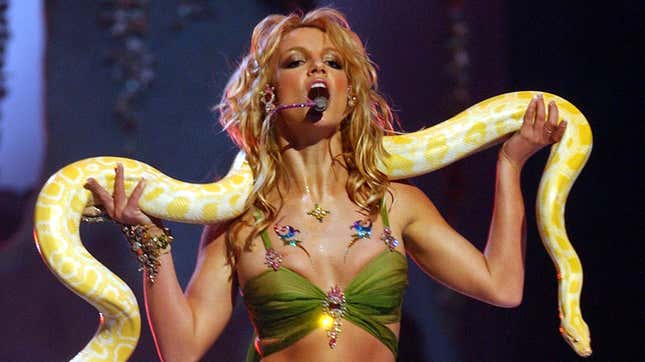

About two-thirds of the way through Britney Spears’ spare and riveting memoir, The Woman in Me, we reach a title drop: “The woman in me was pushed down for a long time,” she writes. “They wanted me to be wild onstage, the way they told me to be, and to be a robot the rest of the time.” The “they” are her conservators, who controlled her life, she says, for over a decade. (“For 13 years, I wasn’t allowed to eat what I wanted, to drive, to spend my money how I wanted, to drink alcohol or even coffee.”)

But the tension between who Spears was supposed to be and who she actually was had been long vexing one of the most plausibly reluctant superstars that the world has ever seen. To hear Spears tell it (or Michelle Williams, whose audiobook reading of Spears’ words has spread virally in clips like the one where she imitates Justin Timberlake imitating AAVE), the part of her career she enjoyed most occurred before her debut album dropped. She recalls the filming of the “…Baby One More Time” video as “probably the moment in my life when I had the most passion for music.” She continues: “I was unknown, and I had nothing to lose if I messed up. There is so much freedom in being anonymous.”

The Woman in Me is a story about identity—that which was robbed from a kid who was thrust into the spotlight at age 12 (via the Disney Channel’s The Mickey Mouse Club) and that which said kid and then woman felt obligated to adopt because of her people-pleasing tendencies and general willingness to play the game that she found herself in. Spears remained a fractured persona even behind the scenes, even well into her adulthood. She writes of “how quickly I could vacillate between being a little girl and being a teenager and being a woman because of the way [the conservators] had robbed me of my freedom.” In observing the landscape of celebrity and those who vie for it, it should be obvious by now that aspiration is not foresight, and there is no preparation in the world for fame. Factor in Spears’ preteen age at her career’s start and the changing nature of media during her commercial peak, and it’s abundantly clear that she had no idea what she was getting into. And then by the time she was in it, it was too late and she was too big. And even if she had wanted to throw it all away, she had people on her payroll to support and then, with the conservatorship, even fewer choices presented. She did what she was told.

This is a particularly telling passage:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-