‘Chasing Chasing Amy’ Shows How Much One Movie Can Shape a Life

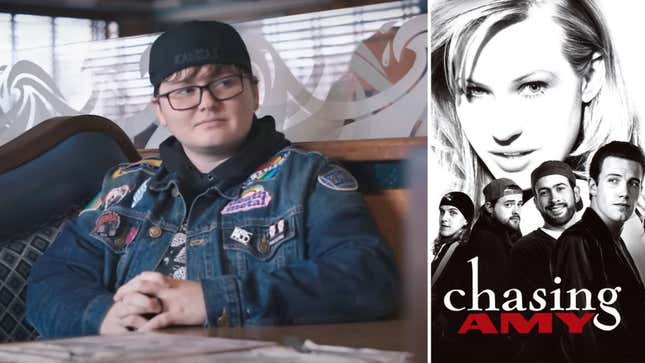

Sav Rodgers talks about his documentary unpacking the controversial '90s rom-com, as well as his transition and an intense interview with Joey Lauren Adams.

EntertainmentMovies

Sav Rodgers’ documentary Chasing Chasing Amy, and by extension his life, would probably look much different if filmmaker Kevin Smith hadn’t asked a simple question during shooting: What are your pronouns? Rodgers had set out to make a film about Smith’s 1997 rom-com Chasing Amy, in which Joey Lauren Adams’ Alyssa, an out and proud lesbian, falls for dudebro Holden, played by Ben Affleck. Specifically, Rodgers was interested in the varying reactions to the movie from within the LGBTQ+ community, which range from admiration to disdain (of course, in the straight guy’s narrative, the straight guy character turns the lesbian).

Rodgers has long sat on the “admiration” side of the spectrum. In 2019, he gave a TED Talk called “The rom-com that saved my life,” about Chasing Amy’s positive impact on his life as a bullied queer youth, which gained the attention of various people involved in the production, like Smith and Affleck. In his doc, which premieres Thursday at the Tribeca Film Festival, Rodgers recounts the impact Chasing Amy made on him after he first watched it at age 12: “Slowly as I started to learn more about my sexuality, this is my only reference point to how I may feel about having a fluid sexuality, and that movie gave me that reference point.”

Chasing Amy was, in part, based on Smith’s romantic relationship with Adams in real life, but it also took a page from the straight guy-queer girl romance of producer Scott Mosier (Smith’s friend and collaborator) and the lesbian-identifying screenwriter Guinevere Turner. (Mosier and Turner met at Sundance in 1994, where Clerks premiered as did Go Fish, which Turner wrote and produced with her then-girlfriend, Rose Troche). Clearly, there was a lot to unpack.

The movie was always going to include elements of Rodgers’ life as well, and we see several scenes of him kind of LARPing as he visits various New Jersey filming locations featured in Chasing Amy alongside his girlfriend (now wife) Riley. But Smith’s question regarding Rodgers’ pronouns while they were shooting an interview changed the course of his life—up until that point, he told Jezebel in a Zoom recently, he never thought he was going to come out as trans. Not in the movie, not in real life.“It was just kind of a spontaneous thing where you have somebody who’s shaped your life in a lot of ways kind of giving you permission to be yourself in some ways [by] asking for clarity,” said Rodgers. “And I was like, ‘Okay, well, I’ll be honest. Yeah, I’ll be honest with myself here.’”

Chasing Chasing Amy juggles a lot. It’s a fond retrospective of the 1997 film that nonetheless wonders aloud, “Why do LGBTQ+ people not like this movie?” It’s an expression of fandom on an extraordinary scale, and yet as personal as Rodgers’ story and relationship to Chasing Amy is, one of the bigger effects of such multitiered storytelling is to show how pop culture can shape a single life.

“I always thought of Chasing Amy as kind of like a cultural Rorschach test, where whatever you’re looking to get out of it is probably what you’re going to get out of it,” said Rodgers. “Whether it’s intentional or not, your expectations or confirmation bias may inform how you read Chasing Amy as a movie, and I’m finding that it also may be that way for our documentary.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-