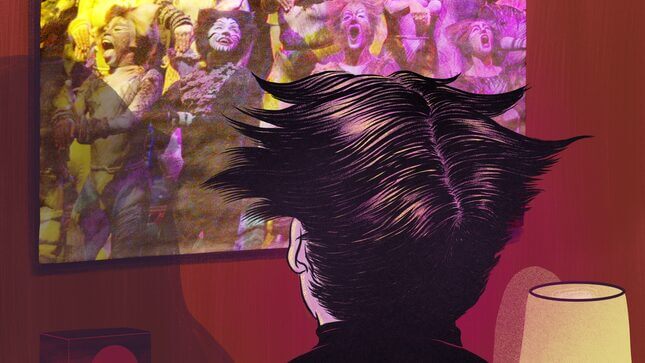

Illustration: Jim Cooke

My first gay experience was with the Rum Tum Tugger.

My second-grade teacher, Mrs. Rosen, illegally staged Cats in our elementary school cafeteria. I was cast as Mr. Mistoffolees, which meant that my mother had sequins sewn into my cat costume and that I shouted “Presto!” after pulling the string on a confetti popper. This was on Long Island in 1986, when Cats was so omnipresent, you couldn’t turn on the TV or walk by a bus stop without seeing yellow cat eyes with dancer pupils staring back at you. The Rum Tum Tugger and I were too young to Rum Tum tug each other; we mostly rubbed each other’s backs while discussing the finer points of Jellicilism.

Cats, of course, had been my first Broadway show. My parents took me to the Winter Garden theater a year earlier, and I’ll never forget the thrill of that overture as the cats came leaping down the aisle, tousling my hair and brushing my arm. I remember feeling part of something illicit; that this junkyard world of fancy cats was foreshadowing, somehow, to a future I couldn’t possibly yet comprehend. I listened to the cast album over and over again on my Fisher Price record player.

Fast forward to 1990: my parents sent me to French Woods Camp for the Performing Arts where I was, once again, a cat in Cats. This time, I was a random chorus cat, wearing a black unitard as I sang the songs and crawled over the laps of the audience (slightly problematic, but this was the ’90s). When my parents came on visiting day, I refused to speak to them because I was getting into character.

My best friend that summer was Skimbleshanks the Railway Cat, a redheaded kid, also from Long Island, who spoke with a lisp and went on to great acclaim later that season playing King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar. I remember feeling an instant kinship with Skimbleshanks, especially when I learned that he had the unabridged Phantom of the Opera cast recording on cassette. (My parents only had Phantom Highlights, so this was like the Holy Grail.) Our friendship flourished, even when our Cats director quit the night before opening because we weren’t invested enough in Deuteronomy’s return after his kidnapping by (*Spoiler alert*) Macavity.

Now that Cats has been reborn as a movie, it’s difficult to reconcile my relationship to this material that is both undeniably bad as a work of art (see: most people’s reactions to Cats) and also the most significant cultural artifact in my life. Cats is comforting to me: I play it when I’m doing the dishes. And when my husband tries to cue up a hip new album on Alexa, I troll him from my computer and turn on Skimbleshanks. We call it Skimblepranks. It keeps our marriage healthy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-