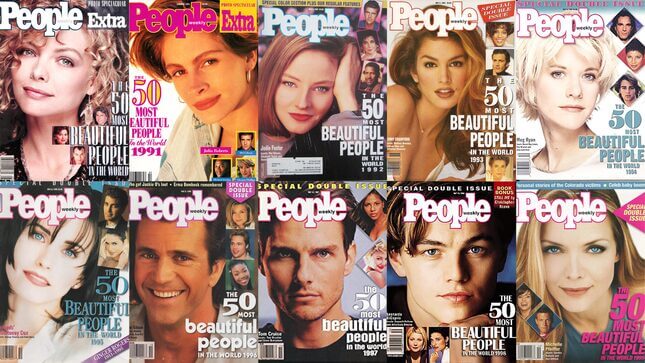

Graphic: Jezebel (Photos: People Magazine)

It’s no surprise that the editors of the very first issue of People’s now-iconic “50 Most Beautiful People” issue were two men: Eric Levin and Roger R. Wolmuth. “They were clueless! Totally clueless,” Maddy Miller, the magazine’s former photo editor for special issues, laughs. “They were great guys, and great editors, but they were completely clueless.”

The inaugural 1990 issue crowned Michelle Pfeiffer, who had recently starred in The Fabulous Baker Boys, as its most beautiful. “[The editors] would have to think about it some, look at her, and then look at her from this angle and look at her from that angle, and then this angle again,” Miller, who was with People for 26 years, reminisces. “Like, oh! Come on.”

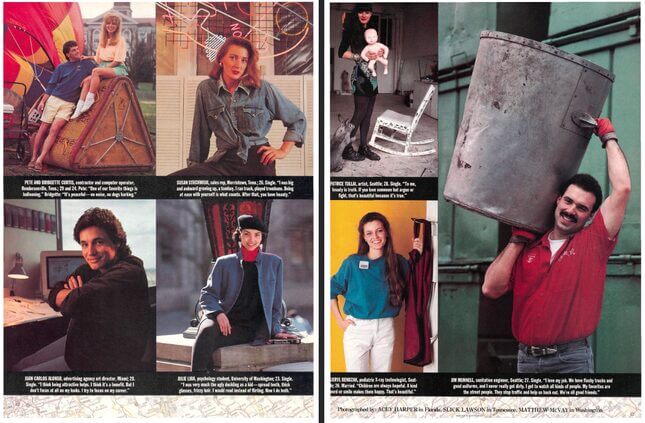

It’s been 30 years since the first issue was published, three decades since it changed the course of People magazine and became a cultural touchstone. Before People was the juggernaut of the celebrity media, it was a magazine “about people.” Hillie Pitzer, the magazine’s longtime art director, described those people as the kind that “my neighbor, my friend, my sister, my mother could relate to.” Pitzer remembers a time when the focus was on human interest stories, and things that really affected people’s lives: drug addiction, nursing home abuse, teen pregnancy, and true crime. All coupled with, of course, features about the personal life of, say, Kirstie Alley or the financial woes of the then-spoiled brat and New York tycoon Donald Trump.

Celebrities always existed in the pages of People, except, exactly that: just people, disrobed of their public radiance. The red carpets were replaced with kitchens, and living rooms, and children’s nurseries with fresh wallpaper and a smiling newborn. It was Vanity Fair for everyone else. Now, People is unabashedly about celebrity—ones in movies and magazines, the ones that become increasingly hard to relate to, even as social media bridges physical and metaphorical distance. It’s an entirely different publication than it was in the 1990s when Miller, Pitzer, Levin, Wolmuth, and others collaborated on the very first roundup of the most beautiful people in the world.

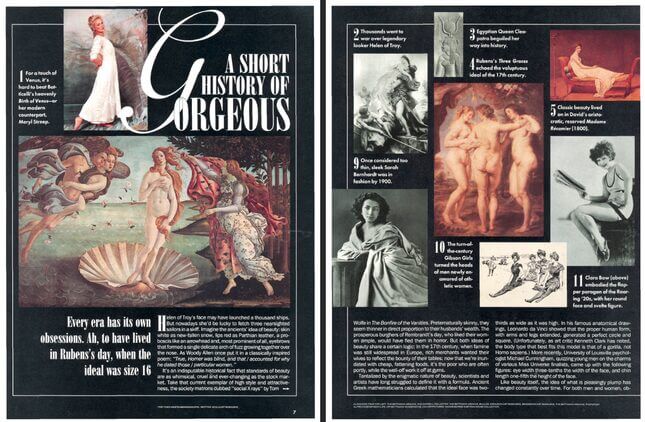

The first feature of the inaugural “Most Beautiful People” issue is titled “A Short History of Gorgeous,” in which the first two photographs are of Meryl Streep and Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece The Birth of Venus. “For a touch of Venus, it’s hard to beat Botticelli’s heavenly Birth of Venus—or her modern counterpart, Meryl Streep.”

It’s an indisputable historical fact that standards of beauty are as whimsical, cruel and ever-changing as the stock market. Take that current exemplar of high style and attractiveness, the society matrons dubbed “social X rays” by Tom Wolfe in The Bonfire of the Vanities. Pretematurally skinny, they seem thinner in direct proportion to their husbands’ wealth. The prosperous burghers of Rembrandt’s day, who liked their women ample, would have fled them in horror.”

Reading the issue now, it’s almost hard to imagine one is still reading People.

In the essay, the writer lays out a grand philosophy of beauty standards, involving famine and poverty and billionaires and the increasing gap between social classes. They quote art critics and psychologists, cite studies about fat distribution in the human body, vivisect Victorian conventions, and in eloquent prose, layout their theory connecting the Puritan Work ethic with movie stars like John Wayne and Robert Redford. “Who knows? One day soon, our standards of beauty may even cease to exclude most of the human race,” the piece intones.

It’s a predictive, almost irreverent takedown of the issue’s own ethos (and very of its era), in ranking 50 socialites and celebrities and ballerinas and artists and musicians. Self-aware, it pokes fun at itself, until the entire issue almost collapses in from the burden of its psychological ennui. As Miller jokes, the issue’s editors were “thinking men,” the type that cited scholars and Victorian philosophers in the opening pages of a tabloid weekly.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-