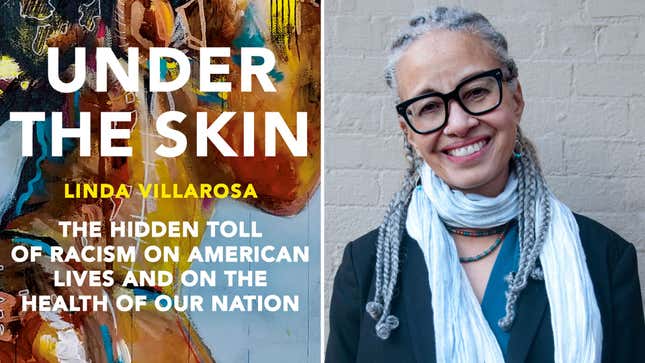

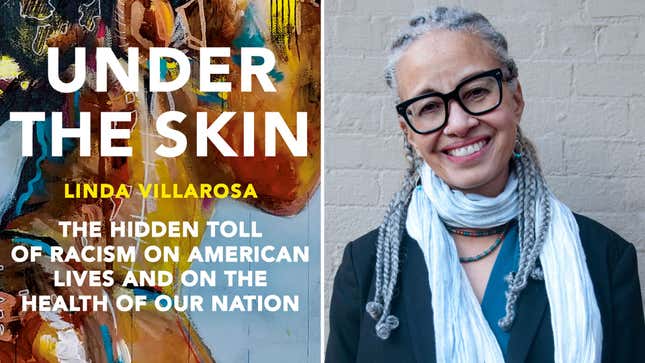

‘Under the Skin’ Charts the Steep Toll Racism Takes on the Black Body

“We’re the canaries in the coal mine as Black people,” said Linda Villarosa, whose reporting first put Black maternal mortality into the national conversation.

BooksEntertainment

When Simone Landrum gave birth in 2017, Linda Villarosa was there to observe as she endured instance after instance of thoughtless and even dangerous care from medical professionals. The anesthesiologist botched the epidural, leaving her with a severe headache and without feeling in her legs. Then, with her OB-GYN unavailable, a team of doctors Landrum had never met before delivered her infant, “taking turns between her legs without addressing her or looking her in the eye,” Villarosa later wrote. Despite all of this, it was a far better experience than Landrum’s prior delivery: Before, doctors had ignored her pain and high blood pressure, and she had nearly bled to death. Her daughter died, six weeks before she was supposed to be born.

What most of the medical practitioners who attended Landrum’s 2017 birth didn’t know, however, was that Villarosa was a writer for the New York Times Magazine. Her article about the treatment Landrum, a Black woman, was subjected to, which Villarosa used to illustrate the broader national crisis of Black maternal and infant mortality, appeared in the publication in 2018 and helped spark a national conversation. It’s just one of many stories of America’s Black health crisis that Villarosa tells in her new book, Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and the Health of Our Nation, which examines the myriad ways in which Black America’s health suffers under the nation’s racial caste system.

Originally, Villarosa intended to subtitle the book “Race, Inequality, and the Health of the Nation,” but instead decided to use a phrase that made the cause of all this unnecessary suffering and death abundantly clear. “While I was still writing this book, I wasn’t really willing to say ‘racism’ so in your face,” Villarosa told Jezebel via Zoom. “I changed it because I thought, ‘Why am I not saying exactly what it is?’”

As the country continues to struggle with the pandemic and a mental health crisis, both of which have disproportionately affected people of color, Under the Skin maps the ways racial bias has shaped the health landscape for all Americans. “We’re the canaries in the coal mine as Black people,” Villarosa said. “We’re sounding the alarm to say, ‘This is what’s happening with us, but it can happen to anyone.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-