Standing in the Doorway: The Dream of a Woman on a Winning Presidential Ticket

In Depth

Illustration: Elena Scotti (Photos: Getty Images)

I was determined to stick it out at the Jezebel offices on Election Day 2016—despite the fact that I was 36 weeks pregnant and my body felt like a wet sack of sand. I wanted to watch America elect its first woman president with my colleagues at this supposedly feminist website. Not as an unqualified victory for all women everywhere, but as an important landmark, nonetheless, one that I knew would bring a moment of collective euphoria. Quite simply, I wanted to witness history; I remembered the elation that had erupted in New York City when the 2008 election was called for Barack Obama, and I anticipated another symbolically important moment where the possibilities for the presidency expanded dramatically. I looked forward to watching America inaugurate its first woman president with my newborn daughter on my lap. Instead, when CNN called Florida for Trump, I went home, because it was clear that the 2016 election would be historic for entirely different reasons. The crash from the heights of anticipation was sharp, immediate, and painful.

Now we’re on the verge of another election; after beginning the Democratic primaries with a historically diverse slate of candidates, it’s once again a white man at the top of the ticket—but Kamala Harris is there, too, running as Joe Biden’s VP. And given that the man is 77 years old, she’s an important part of the proposition they are making to voters, charging around America in her Converses.

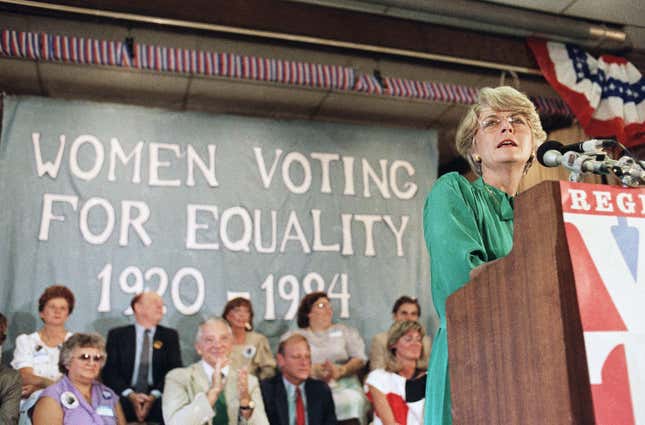

We’ve been here before; Harris is the third woman to run as VP on a major-party presidential ticket, and of course, previous presidential campaigns by women culminated in Clinton’s disastrous loss in 2016. All these years, and still no woman elected to either the top or the second-string spot—a dream that seems so close, yet constantly recedes into the distance. “A door has been opened that can never be closed again,” 1984 Democratic VP nominee Geraldine Ferraro said in her concession speech on the night she and her running mate, Walter Mondale, lost to Ronald Reagan in a blowout. The door may be open, but it’s proven nearly impossible to walk through. Now Harris stands on that threshold as a woman of color, giving her candidacy a spectacularly historic dimension—and attempts, once again, to pass through.

The history of women running for president goes back all the way to the 19th century before women even had a nationwide right to vote. The colorful Victoria Woodhull, a free love proponent, businesswoman, and spiritualist, among her many other qualities, ran in 1872 on a platform of equal rights and suffrage for women; she spent Election Day in jail on obscenity charges after accusing the prominent minister Henry Ward Beecher of adultery in her newspaper.

Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine, the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress, had a better run of it in her 1964 campaign, although she didn’t get very far, either. Smith initially found her way into politics when she ran to replace her husband, who died, in the House of Representatives. This was fairly common at the time: As a New Yorker piece explained: “Clyde Smith’s plea to his constituents drew upon a convention that emerged after women won the vote, in 1920—the “widow’s mandate,” which involved appointing or advancing by special election a woman to fill out the congressional term of a husband or other male relative.” The idea was that a wife would faithfully carry out her departed spouse’s agenda, without going rogue.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-