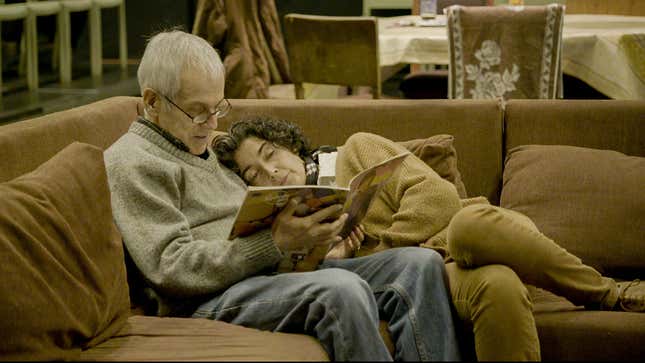

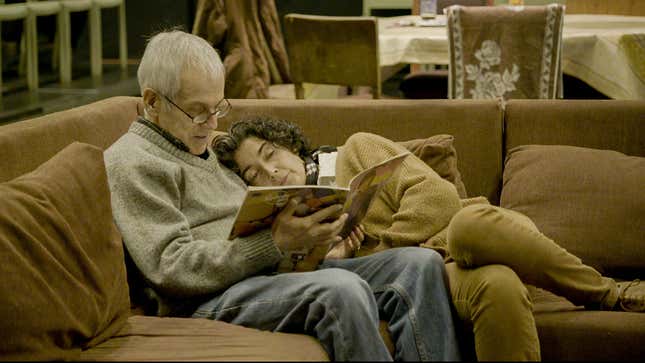

Devastating Doc ‘The Eternal Memory’ Captures Love in the Time of Alzheimer’s

"It’s a film about a couple," director Maite Alberdi told Jezebel. "It’s not a film about a disease."

EntertainmentMovies

Well into the documentary The Eternal Memory, a bitter irony sets in. As a journalist, Augusto Góngora fought for the preservation of national memory in his native Chile, and yet his own memory is dwindling away. During the oppressive Pinochet dictatorship, Góngora had edited a newspaper for the opposition and reported on crimes of the Pinochet regime on underground television. He then co-wrote Chile: The Forbidden Memory, which detailed the regime’s extensive human rights violations. In a note written to his wife Paulina Urrutia, actor and former minister of the National Council of Culture and the Arts, and read in the movie, Góngora said: “Memory is forbidden but this book is stubborn.”

When we meet Góngora in Chilean director Maite Alberdi’s documentary, those days of journalism are long behind him. He is effectively retired and in a state of cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s disease, tended to by a loyal and preternaturally patient Urrutia. Cutting back and forth in time, The Eternal Memory, which opened last week in New York and today in Los Angeles, portrays the domestic life of the couple, rounding it out with dispatches from their past, often via professional video footage and home movies. It is largely devastating, but it’s often shocking when it’s not—particularly early on, when Góngora and Urrutia sometimes smile and laugh about Góngora’s lapses. But as the documentary, which was shot over the course of nearly five years and wrapped in August 2022, progresses, the situation becomes more fraught. Góngora is increasingly agitated by his own flashbacks to the days of the Pinochet regime. Urrutia’s patience, meanwhile, remains unwavering.

The Eternal Memory played Sundance this year, where it won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary. Góngora died in May, less than a year after Alberdi wrapped shooting. Jezebel talked to the director about the intimate project and Góngora’s legacy. An edited and condensed transcript of our discussion is below.

JEZEBEL: I read in the press notes that you followed Augusto and Paulina for about four years.

MAITE ALBERDI: Almost five.

That’s a long time to be filming a documentary, right?

I usually shoot for five years. I am used to following people for a while.

Why that much time?Because reality takes time to develop. People and life do not change in one month. To see process and to see narrative and dimension of time, you need to be following for a while. And in this case, I always said at the beginning I wanted to be with them until the end, and if the end was 10 years, I was going to be there 10 years.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-