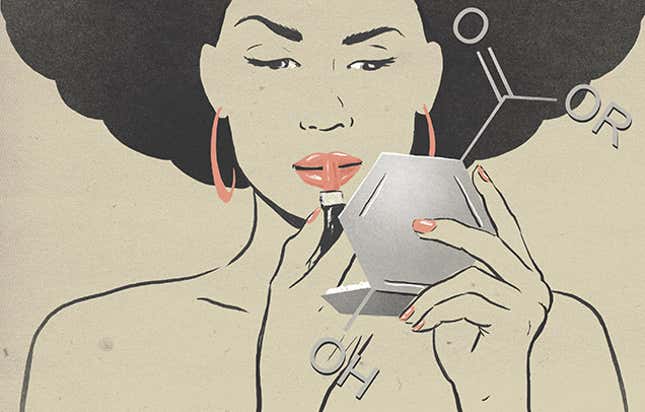

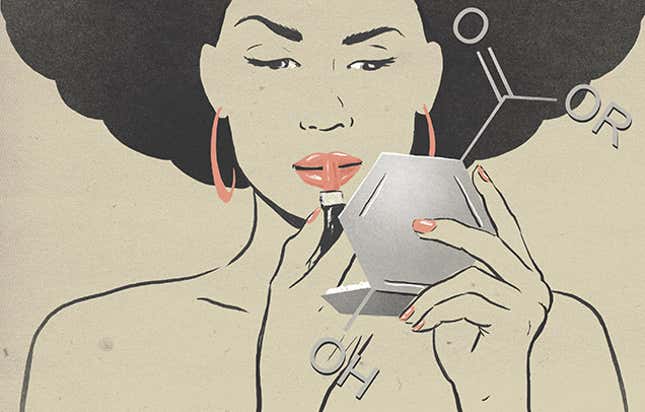

Is Your Makeup Giving You Cancer?

In Depth

In 2012, Shannon Bindler threw away all of her makeup. Bindler is a self-described “life stylist” and the creator of Sole Prescription, a company that specializes in inner and outer make overs. She describes her life passion as the “conscious connection between fashion and spirituality.” Bindler has a master’s in spiritual psychology from the University of Santa Monica and spent the early part of her career as an editor of a yoga magazine.

Bindler told me that she’s always been very conscious about what she puts in her body. But it was in 2012, that she became aware of what she put on her body. Why the change? Well, she was pregnant and the swell of her baby and the heightened awareness of her body made her rethink her approach to her skin.

She explains, “Your skin is the largest organ on your body and we put lotions and cosmetics on it every day and our body absorbs that.” Additionally, Bindler did a lot of research and became convinced that the phthalates and parabens in her cosmetics were harmful. She points to the Environmental Working Group as a site that ultimately convinced her to go non-toxic.

“It just can’t be good to put all those chemicals on our bodies all the time,” she said. So, she tossed her makeup and bought all natural. She hasn’t looked back since.

The change wasn’t cheap. Bindler laughed when I asked about the cost. “Yeah,” she said, “it’s a bit more expensive.”

“A bit” is a bit of an understatement. I dug around online and in my local Walgreens to compare the prices and I found that there is at the least a $10 difference between cosmetics marketed as non-toxic and your average drug-store quality makeup, if not more. And it’s usually more, a lot more.

But if safety is so important, why is it priced so high? Is being cancer free a luxury of the rich? Is this cancer price gouging or are companies’ just taking advantage of our chemical hysteria?

Organic, non-toxic personal care products are a rapidly growing industry. Jessica Alba’s The Honest Company is looking to get in on the action with an organic, cotton tampon (she’s not the only one) and Gwyneth Paltrow is reportedly developing her own organic cosmetics. Although both women claim to be one of us, GOOP makes my wallet shake in fear when I log onto the site and The Honest Company diaper bundle is $79.95 a month. To compare, I pay half of that for my baby’s Pampers shipped from Amazon. And Pampers are on-brand and expensive. There is definitely money to be made allying our chemical fears.

In a recent webinar about how cosmetics are made (because nothing sounds fun like a webinar about the product cycle of your lipstick), I was interested to hear Beth Lange, Ph.D., Chief Scientist for the Personal Care Products Council, deride this organic movement as just marketing. The Personal Care Products Council is a trade association with members that range from Almay to M.A.C. So, yeah, they are Big Makeup. They have a stake in settling down these upstart organics.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-