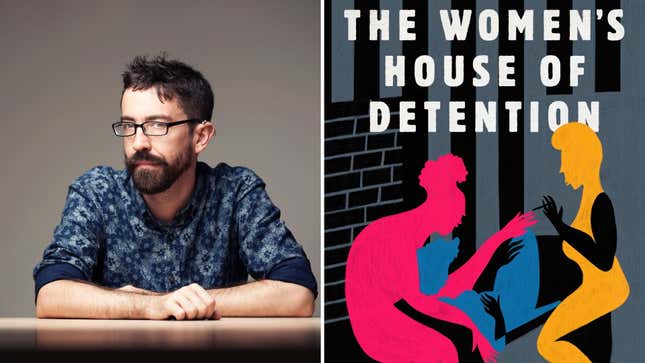

‘The Women’s House of Detention’ Illuminates a Horrific Prison That ‘Helped Define Queerness for America’

Hugh Ryan's new book offers portraits of the forgotten queer and transmasculine people who made LGBTQ history.

BooksEntertainment

Photo: Irving Haberman/IH Images

Most articles about the legendary LGBTQ activist and “bad-ass Super Butch” Jay Toole lead with the fact that she’s a Stonewall veteran and feature her account of those six days that changed American history. But Toole also has some pretty shocking and important stories to share about another historic building, just 500 feet away from the Stonewall Inn: the Women’s House of Detention.

In an interview with author Hugh Ryan, Toole described one of the many times she was taken to the prison while she was living on the streets. Incoming detainees were brutalized with physician-administered forced enemas and cavity searches, and during one particular assault, she said, “It felt like his whole arm went in there.” Toole was left “covered in blood” and immobilized by pain.

“And they didn’t do nothing,” she told Ryan.

According to one 2017 study, more than 40 percent of the people held in America’s women’s prisons are queer, and, as Ryan notes, this figure was surely even higher in years past, when jails could contain people arrested for “crimes” like wearing pants. The House of Detention, which stood in New York’s Greenwich Village from 1929 to 1974, once held famous queer women including Andrea Dworkin and Angela Davis, but despite its history, the prison has slipped out of local memory. (One of its most prominent pop culture representations came via a little-seen and widely panned 2004 David Duchovny movie about a straight, white boy.) Though it’s been treated as a footnote to more celebrated LGBTQ sites of resistance, the facility, Ryan writes in The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison, “helped make Greenwich Village queer, and the Village, in return, helped define queerness for America.”

“These files are incredible. I found wedding rings in these files. I found photos, love letters, poems.”

While working on his first book, When Brooklyn Was Queer, which examined the borough’s hidden LGBTQ history, Ryan noticed that more than one of the figures he profiled had been arrested and taken to the House of Detention. Then, he noted the prison popping up in queer history after queer history. “Suddenly it was like the House of Detention was jumping out at me everywhere,” he said. “I was looking through Audre Lorde and there it was, and I was looking through Joan Nestle, and there it was.”

He was determined to tell the story of the prison not from the institution’s perspective, but via the women and transmasculine people whose lives it upended. For the necessary biographical details, he turned to the Women’s Prison Association, which funded social workers at the House of D, as the prison was known to locals. Its archives are held at the New York Public Library, and in them Ryan found a treasure trove.

“These files are incredible. I found wedding rings in these files. I found photos, love letters, poems,” he said. “Some of these files ran like 500 pages and covered 40 years. It was shocking.”

Ryan first wrote about the life of of “Big Cliff” Trondle, whose early arrest for “masquerading in men’s clothing” caused him to write to President Woodrow Wilson and ask that he not be forced to wear a dress to court, in When Brooklyn Was Queer. However, Trondle disappeared from the historical record during his youth, until Ryan found his WPA records. “The moment where I found Big Cliff’s file, I actually yelled out loud in the library,” Ryan said. “I wasn’t even looking for it. It was just there all of a sudden. And I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is the next 30 years of his life.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-